Red is the color of primal energy. It is the color of passion, love, beauty and of strength, motivation and physical drive. Red warns us, catches our attention, raises the blood pressure and quickens the heartbeat.

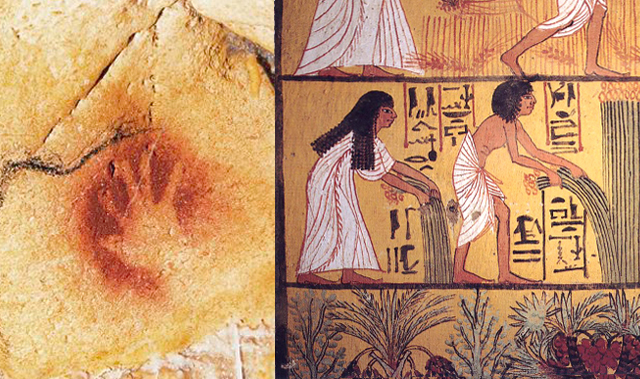

Texts from antiquity tell us that the same artisans who manufactured pigments also made medicinal preparations and cosmetics. Color was an important motor for scientific, medicinal and artistic development.

Through the centuries, search for the purest, most vibrant and long lasting hues helped stimulate growth and development. It led to discovering new continents, experimenting with alchemical then scientific methods and establishing the crops, trade and industrial production, which were fundamental to growing world economies.

According to Pliny, a 1st Century AD historian, Egyptians used Madder, cochineal, and archil (a red-producing lichen) to dye the red linen textiles found in the Old Kingdom tombs of the Nile Valley. They also invented mordanting, a treatment of fibers with chemicals that allows the dye to adhere better, thus increasing colorfastness.

Following the Egyptian formulas, Roman frescoes used well known pigments. A few have panels painted entirely with very costly pigments, such as cinnabar vermilion (a sulfide of mercury).

The famous Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii, whose walls have a background of dazzling Pompeii red, is an example. The raw material was imported from Almaden, in Spain, to Rome, where it was converted into pigment.

To obtain the bright red hues, the cinnabar had to be purified; then synthesized, then ground to the correct fineness. Any mistake and it would turn black. Because of its rarity and expensive production, this red was a status symbol.

In Medieval Europe, as in Rome, the use of vivid dyes was only for the wealthy. The higher quality dyes and mordants were still imported and extremely expensive.

The Madder plant (Rubia Tinctorum) was to be found locally in many parts of Europe – cultivated in Normandy, Spain, Sicily and Lombardy. The root was dried and milled, to yield a paste or powder.

Pigments made from Madder root, varied from rose to brown and were used by contemporary painters of the day. The color was highly valued in the Middle Ages for the dying of festive clothes, such as wedding apparel. In a way, Madder democratized this color, making the bright red of the upper classes available to the common people.

Alchemists carried out the research in chemistry and the technology of pigments in the Middle Ages. They perfected techniques of heating, maceration, studied extraction and distillation, and experimented with new products such as mineral acids.

This stimulated new ways to produce colors: a deep shade of red is created by the combination of mercury and sulfur. The color created by these chemicals is Vermilion. Naturally occurring Vermilion is called Cinnabar. Below, in its raw form.

Meanwhile, the discovery of the Americas overturned the whole dye trade, especially the market for red—madder, cochineal, and brazilwood. The costly dyes which produced the vermilion-scarlet reserved for the finest wool and silk had replaced Tyrrian purple as the official color of royalty and high officials of the Church. (ie. Cardinal Red)

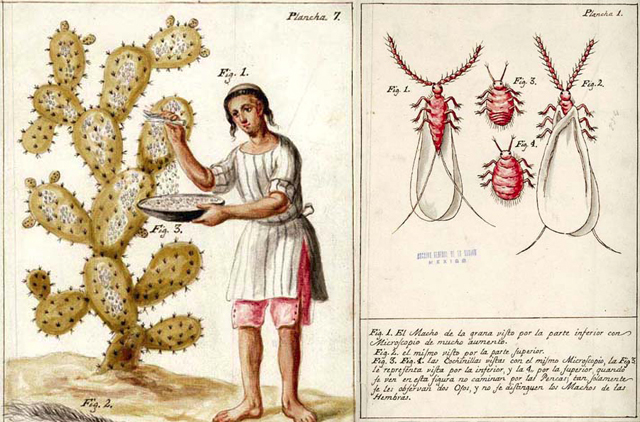

The prosperous cochineal trade was suddenly overwhelmed by the massive importation of cochineal from the Americas. Soon after their arrival, the Spanish discovered regions in Mexico where prickly pear cactus (where the cochineal insect lived) was cultivated. The use of cochineal red dye in the Americas dates from 400BC.

The following image on the left is a drawing from 1777 of a Native South American harvesting Cochineal red; on the right, an illustration of the cochineal insect.

Below, grinding of the cochineal insect to produce the red pigment; a cochineal woven belt; a cochineal plantation.

The word cochineal derives from the Aztec name for the dye, “nochezli” or blood of the prickly pear, transcribed by the Spaniards as “cochinilla”. In 1560, the galleons unloaded 115 tons in the port of Seville.

Cochineal crimson became immensely popular; at Versailles, Louis XIV set a fashion by covering his walls and armchairs and hanging the curtains of 435 royal beds with ruby damask. Notice his red heeled shoes in the following portrait — now we know where that fashion probably started!

While it is comparatively easy to dye animal fibers red — such as silk and wool — cotton was much more difficult; and until the 17th Century only India knew how. When the use of cotton spread to Europe around 1700, dyers were eager to learn India’s secret — known as Turkish red.

The fabric was soaked in animal fats and excrement and air dried, to prepare it for dying in a madder bath where bull’s blood was added. The cultivation of Madder, which had fallen into neglect, was revived and experts from Turkey were brought to Europe to work the new red cottons.

Red is a primary color between the orange and violet tonalities. When we think of fire — heat — we think of red. It is the hottest of all the colors and experiments show that red-painted walls actually increase the temperature of a room. Just as cool colors encourage rest and meditative relaxation, so hot colors promote activity. Red stimulates alertness — warning lights, stop signs, fire extinguishers — but too much hot red can become distracting and draining.

A little red goes a long way. Of all the color vibrations, red is the slowest, so it can become heavy and oppressive. Red appears to advance toward us, making rooms look smaller and more intimate. These spicy hues create a cozy and inviting refuge. Usually just a red pillow on the sofa, or a red accent is enough to give life to a room. The following photos are from Sara Kaye Photographers.

Red always feels rich. And because it is the color of blood, of life itself, of passion and primary instincts, it has become the color of love. Hearts, valentines, women in red, all point to the allure and magnetic attraction this color holds.

Amazing post, one of the most interesting points to me is how the search for beauty might have been the engine of human economic development..

Yes! Imagine color as commodity trading.

If anyone wants to read more about the cartulul aspects of how cochineal red came from South America to Europe then they might want to read A Perfect Red by Amy Butler Greenfield. It’s one of those historical books told as a story and I enjoyed the read. It only touches lightly on the artistic aspects, though.

Thanks for this, the dyes and their history and chemistry was one of my favorite things in the study of textiles in college. I especially loved the purple made from mollusks in the Mediterranen, which was “royal purple” due to it’s scarcity and expense. I wish someone would do that story.